(Part 1)

Introduction

Once it is determined who is granted access to the system and how this system is going to be paid for, the next step is discovering how these health care services are going to be delivered. After all, the point of our nation becoming part of the noble cadre of nations that recognize access to health care for all citizens as a civil right of some kind is to actually treat sick people. Sounds like a given, but how do they go about doing it?

Primary Care – The PACT Model

The key to delivery in the VA is through the Primacy Care Provider (PCP). There is one doctor (MD), or nurse practitioner (NP) that is charged with providing the basis to all services to an individual Veteran. The team also has a small cadre of Registered Nurses (RN), Licensed Practical Nurses (LPN),

The key to delivery in the VA is through the Primacy Care Provider (PCP). There is one doctor (MD), or nurse practitioner (NP) that is charged with providing the basis to all services to an individual Veteran. The team also has a small cadre of Registered Nurses (RN), Licensed Practical Nurses (LPN),

Nursing Assistants and Medical Support Assistants (MSA) that work in support of the PCP. This is in effect, a small clinic that operates similar to many health care systems and even at private clinics.

What the PACT team does, is provide the Veteran with general services, also a given since the MD is typically a general practitioner. This team should handle routine services, and also does the grunt work in terms of keeping track of medical history. They provide this based on particular medical criteria designed to stay abreast of common health factors affecting the given population. As noted in the previous essay, most of the Veteran population is older and male.

This means the PACT can focus on the types of issues older men typically face. Examples of such conditions include obesity, hypertension, diabetes or any condition that will worsen over time if a relationship with a physician is not maintained. If a condition worsens, the PCP will know about it and be in a good position to alter his or her plan of care. This proactive approach is often pointed out by advocates of single payer health care systems as a feature of these systems since most of the time healthcare in the United States is a reactive proposition. Reactive in the sense that most people will simply wait until that bump gets bigger, or that knee becomes too unbearable to walk on, or it hurts too much to urinate in the morning before finally making an appointment to see a doctor.

This means the PACT can focus on the types of issues older men typically face. Examples of such conditions include obesity, hypertension, diabetes or any condition that will worsen over time if a relationship with a physician is not maintained. If a condition worsens, the PCP will know about it and be in a good position to alter his or her plan of care. This proactive approach is often pointed out by advocates of single payer health care systems as a feature of these systems since most of the time healthcare in the United States is a reactive proposition. Reactive in the sense that most people will simply wait until that bump gets bigger, or that knee becomes too unbearable to walk on, or it hurts too much to urinate in the morning before finally making an appointment to see a doctor.

Symptoms may not appear until it is too late for treatment to be effective for many fatal diseases; the system is more likely to catch an underlying condition while it is most effective to treat in this proactive system. Catching these conditions early on has the added benefit that it is often more cost effective than catastrophic treatment (6).

There are studies that Longman cites in his book that suggest a correlation to this approach leading to better outcomes versus the patient waiting until the symptoms get too unbearable (6). There are some studies that go so far as to say that VA patients live a longer life, in spite of disability, alcoholism, PTSD, et cetera, being more frequent than in the general population. Even studies with outcomes in specific areas cited as performing better than the private sector (6). The overall cost of such a system also has a tendency to be lower than the fee for service model. One study from 2004 suggested all VA services provided during FY 99 if reimbursed at Medicare rates would be result in an estimated 17% higher cost to the taxpayer (1).

Specialty Care

This is where things get a little more complicated. Consider what many third party insurers require of their customers to see a specialist. Typically, if a customer wants their insurance to pay for specialty care they will have to first go to a primary care clinic to initiate a referral. What this does for the insurer, is inform them the requested service is medically necessary. This necessity is important to insurers because specialty care providers have a tendency to provide services that are more expensive than their general counterparts. Similarly, in order to see a specialist, a Veteran must first see their PCP. This step allows the PCP to discuss all of the options available to the Veteran and if their condition truly warrants the expertise of a specialist they will initiate a consult.

The consult is essentially a documented source of communication between the PCP and the specialist. Once the PCP enters the consult, the specialist is notified via a provider alert on the Electronic Health Record (EHR) Software. They will review the PCP notes, review the Veteran’s charts if necessary, and if the specialist agrees the service is necessary the specialty clinic’s MSA will contact the Veteran to schedule an appointment. At this point, the treatment varies with the Veteran’s circumstances. It could be an evaluation, a noninvasive outpatient treatment or perhaps a surgery needs to be scheduled with an inpatient stay. All of these specific circumstances are documented on the consult. Once the service is provided, the specialist will document their findings in the EHR to be ultimately reviewed by the PCP. If the specialist does not agree the services are needed, the reason why is documented and the consult is discontinued. If the specialist needs more information, a lab for instance, this will be documented and sent back to the PCP, this way the specialist has every resource available to make an informed decision.

Drugs–the legal variety.

The reason often cited for the efficacy of VHA versus private sector hospitals is the VistA EHR system. It allows a somewhat simple integration between clinics as discussed in the previous sections. It also allows medical data to be stored easily, and later used for research purposes. During the Clinton administration, Ken Kizer, the SecVA at the time, implemented a prescription drug formulary by researching this data as well as recognizing that once Veterans go to the VA they typically stay there. For whatever reason why they stay, they identified they were there for life.

‘If you are going to have your patients for five years, ten years, fifteen years, or life,’ explains Kizer, ‘there are both good economic and health reasons why you would want to use the more expensive drugs. You have a population of patients who are at high risk for sclerotic heart disease, and you’ve got them for life. You make a different decision about what’s on your drug formulary than you might if you knew you only had them for a year or two.’ (6)

What the researchers were able to do with this was create a formulary that determined what drugs worked long term. When the FDA approves a drug, there typically is no long term research into the drug’s efficacy, only if it does what it claims and if it is safe for use. What this means is the VA will only prescribe drugs that have well-known, established effects, but also have been around long enough to be on the generic market. If a new prescription drug treatment hits the market, it is almost certain the VA will not add it to their formulary, even if the drug is truly is a medical breakthrough, as discovered with the new Hepatitis C drug (7). While it was later approved, it required a cost/benefit analysis on the cost of treatment at the VA for hepatitis C before they were able to add it to the formulary. The result is a system that according to the Heritage Foundation costs significantly less than Medicare Part D but presents its patients with no choice whatsoever in their prescriptions (3).

The VA formulary is created through access restrictions on drugs. For drugs to be covered on the formulary, their makers must list all of their drugs on the Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) for federal purchasers at the price given to the most favored nonfederal customer under comparable terms and conditions. Additionally, drug makers must offer the VA a price lower than a statutory federal price ceiling (FPC), which mandates a discount of at least 24 percent off the non-federal average manufacturer price (NFAMP), with a rebate if price increases exceed inflation (3).

Otherwise, the VA negotiates pricing based on volume, as they are the largest health care provider in the country. The drug companies that sell to the VA recognize that it is a closed system and there is little chance of market distortions from below market priced VA drugs. It is also small enough as a portion of the entire health care market, that they are able to break even by selling non-generic prescription drugs elsewhere (3).

Scheduling

Everything in the previous sections of this essay is utterly meaningless if Veterans cannot get an appointment.

The thing is, most major hospital systems and private practices do not worry too much about whether or not they are able to schedule patients in a timely manner. The reason being, they have many fixed costs that are baked into their operating budgets. Paying for the cost of operations requires treating patients. If they can’t get patients into beds, they go under–kind of like when airlines have no passengers. The private sector is also large enough at the moment that if a patient cannot be seen at one place, they can find another. In the grand scheme of things it is about as difficult to schedule an HVAC technician as it is to schedule an appointment with a private doctor—it just depends on where you live, and the local supply and demand for services.

The thing is, most major hospital systems and private practices do not worry too much about whether or not they are able to schedule patients in a timely manner. The reason being, they have many fixed costs that are baked into their operating budgets. Paying for the cost of operations requires treating patients. If they can’t get patients into beds, they go under–kind of like when airlines have no passengers. The private sector is also large enough at the moment that if a patient cannot be seen at one place, they can find another. In the grand scheme of things it is about as difficult to schedule an HVAC technician as it is to schedule an appointment with a private doctor—it just depends on where you live, and the local supply and demand for services.

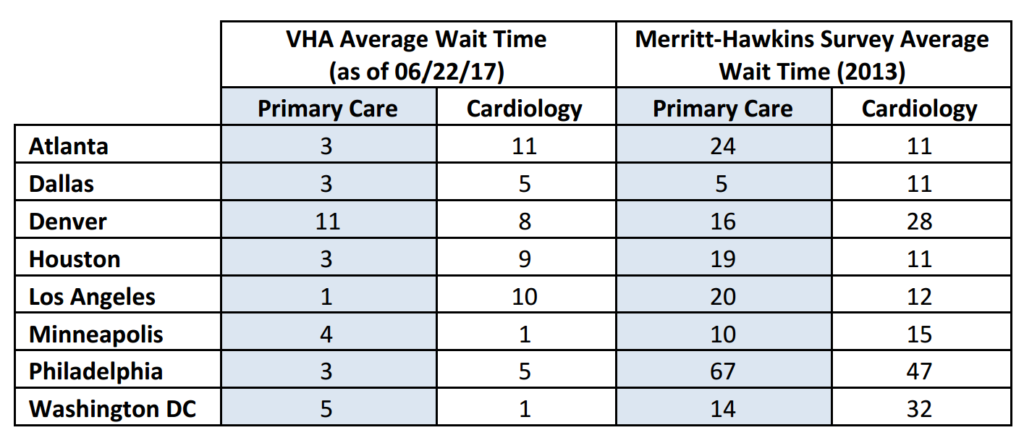

Because of this, it is often difficult to find an apples to apples comparison for scheduling times. In 2014, Merritt-Hawkins published a survey on Medicare/Medicaid acceptance rates and average wait times for a number of US Metropolitan areas (2). Unfortunately, their survey uses 2013 data and is limited to a few clinic types. The VA does have a public website that currently presents average wait times at all their facilities, for a similar number of clinic types (4). For purposes of brevity, only Primary (or Family) Care and Cardiology average wait times will be displayed here by number of days. The references section has links to both resources in case further research is desired.

Ruminations on Primary Care, Specialty Care, Drugs and Scheduling

While the scheduling numbers in the area listed appear comparable or better than their private sector counterparts there is something that should be mentioned here: these data were made available as a result of a well-known scandal involving the manipulation of the wait times first identified in Phoenix, but later found to be endemic of the system as a whole. Here are a few other examples:

Tucson: https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-14-02890-72.pdf

VISN 6 (VA, NC): https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-16-02618-424.pdf

Houston: https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-15-03073-275.pdf

Colorado Springs: https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-15-02472-46.pdf

Providence: https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-15-05123-254.pdf

Cincinnati: https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-15-04725-272.pdf

The VAOIG website is full of these. Unfortunately, bottlenecks within the system can occur. With a large number of people congregating into urban areas, it is very likely to happen in a hypothetical single payer system. Keep in mind the VA only provides care for a small minority of Americans (around 9 million) and scaling the system for the entire population is unlikely to make it work any faster, this is the practical experience in other countries as well. There is also the question of coordinating care with a specialist. So to recap the consult management practice goes like this:

AH! ➔ Appointment with PCP ➔ PCP Agrees and writes up a consult ➔Specialist receives consult and reviews ➔ Specialist accepts and schedules appointment ➔ Treatment ➔ Specialist documents treatment ➔ Specialist informs PCP of treatment ➔ Re-evaluation by PCP if needed.

AH! ➔ Appointment with PCP ➔ PCP Agrees and writes up a consult ➔Specialist receives consult and reviews ➔ Specialist accepts and schedules appointment ➔ Treatment ➔ Specialist documents treatment ➔ Specialist informs PCP of treatment ➔ Re-evaluation by PCP if needed.

Each of these steps requires human input; miss a step and the entire process stops. Stop early enough and treatment may never be given at all. One of the findings from an investigation determined there was little oversight at the time of the investigation of the process at all, which likely lead to unnecessary deaths (6). The prevailing issue with government systems such as these is lack of accountability.

In terms of prescription drug pricing, the VA formulary only works because it is a closed system. Scaling it up will create a massive market distortion that according to the Heritage Foundation, will only drive up costs (3). Consider the formulary is based on restricting the drugs it will pay for, and what doctors can prescribe. This will result in shifting costs to new medications for those willing to pay for it. There is also the matter of the formulary’s insistence on using generics. Generic drugs are made by a limited number of manufactures and if the only thing the hypothetical single payer will pay for are generics and the physician is required by law to only prescribe generics, it will only result in a temporary shortage due to the spike in demand. When coupled with the price controls it is probably going to take these companies longer to increase their manufacturing capacity due to limited funding. Of course if their lobbyists are half as good as they are rumored to be, they might avoid that. Not to mention the obvious result of, “billions of dollars in averted research and development expenditures by drug makers, forgone investment in an untold number of new drugs, and the considerable loss of valuable research and science jobs (3).”

Finally, there is little evidence that profit motive automatically results in poor outcomes. An informed pedant might throw out Roemer’s law. Which postulates that in the for profit model with an insured patient population, every hospital bed will be full. If the hospital finds that they are not balancing their books with primary care, they will simply shift their resources to providing a higher paying specialty—like cardiology. It is in this way they can maintain their patient population and continue to keep their revenue streams in place. If a patient needs a cardiac catheterization, they are probably going to be comforted by the fact the hospital they are at performs the procedure thousands of times a year. Given the procedure involves a surgeon threading a device through a vein in the groin and then insert a device into or near the heart, the patient might think of this as a feature rather than a bug. Finally, even if there are benefits to the “proactive” approach the VA system currently uses that can materialize in a hypothetical single payer, the argument this can only be achieved with a state-run system without the profit motive is made out of ignorance of the industry or dishonesty.

Why? Because there happens to be a similar for-profit system, that apparently made $504 million in Q1 2016 (8). While they are only available in a few areas, it just so happens they specialize in the same type of fully integrated, proactive approach to care that is touted as the feature of state run systems.

Their EHR isn’t a relic from the 1970s either.

References

- Nugent, Gary et al. Value for Taxpayers’ Dollars: What VA Care Would Cost at Medicare Prices. Medical care Research and Review, Vol. 61 No. 4 (December 2004) pages 495-508. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1077558704269795

- Merritt-Hawkins. 2014 Physicians Appointment Wait Times and Medicaid and Medicare Acceptance Rates. (2014) pages 1-32. https://www.merritthawkins.com/uploadedFiles/MerrittHawkings/Surveys/mha2014waitsurvPDF.pdf

- Angelo, Greg. The VA Drug Pricing Model: What Senators Should Know. The Heritage Foundation, No. 1420 (April 11, 2007) 1-4. http://s3.amazonaws.com/thf_media/2007/pdf/wm1420.pdf

- Department of Veterans Affairs. How Quickly Can My VA Facility See Me? http://www.accesstocare.va.gov/Healthcare/Timeliness

- Longman, Phillip. Best Care Anywhere. Polipoint Press, February 2007.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). Report 14-808 VA Health Care Management and Oversight of Consult Process Need Improvement to Help Ensure Veterans Receive Timely Outpatient Specialty Care. http://www.gao.gov/assets/670/666248.pdf

- Reid, Chip. VA can’t afford drug for veterans suffering from hepatitis C. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/va-cant-afford-drug-for-veterans-suffering-from-hepatitis-c/ (06/22/2017)

- Rauber, Chris. Kaiser Permanente: First quarter profits down, but revenue and enrollment up. http://www.bizjournals.com/sanfrancisco/blog/2016/05/kaiser-permanente-healthcare-50-percent-drop.html (06/22/2017)

What the fuck could go wrong with government owning healthcare? i mean, look at how successful the VA has been!

I know exactly how people like my dad will respond to that: “You have a choice to get VA treatment or not. Single-payer only works (ahem, “works”) if everybody gets the same choice and you can’t opt out of it! I support single payer b/c large pool = lower insurance cost b/c magic, or something!” IOW, they would rather everyone get equally shitty options than accept that not everybody can have an equal outcome. Infuriating.

but when a man masturbates to a woman he know in real life without her consent, that is telepathic rape. It’s sick. It even affects the victim although she may be unaware but it lowers her energy.

We can all be poor and sick together. That’s the inevitable outcome of every socialist scheme.

well that was a copy and paste fail.

I’m not exactly sure what to call that.

I vote for “metaGilmore”

the Latch?

I’m raping you right now!

…

they would rather everyone get equally shitty options

And everyone won’t get shitty options. If private insurance is still legal you better believe the political class will be getting better care. Happens up here in Canada to the point where the Premier of the province with apparently the best heart disease hospital in the country will opt to go to the U.S. instead for heart surgery.

The US gets a lot of medical tourism, which is strange, considering how horrific our health care obviously is, from hearing socialists talk.

That’s because Americans are extremely spoiled when it comes to healthcare. If you ever do end up in a public system you’ll have to pour hundreds of billions into it to keep it even close to what the average insured has now.

It’s also an open secret that people who work in the various Canadian provincial health care systems tend to get preferred treatment when one of their own gets sick. When the medial meniscus in my right knee blew out, I was told that I’d have to wait 30 months for an operation. Meanwhile, I met a nurse whose daughter had the same injury — she presented herself to the ER of our local hospital in the AM and had a surgery scheduled for later that same day. (In fairness, that was unusually fast — the stars were aligned for the young lady — but even a slower response would have been on the order of a few days, not 2.5 years like it was for me.)

There are also specific opt-outs built into the Canada Health Act to allow for much more timely treatment of police officers and members of the military.

The commonly-held belief that “everyone in Canada is in precisely the same queue and thus everyone is treated fairly” is dead wrong. And even if it were correct, why does the “fair” standard of care have to be “meh”?

The example I always use is comparing medical faculties (public) to dentistry ones (private). Dentists tend to have top of the line equipment, extremely well trained staff, even high quality chairs, etc. Meanwhile I had an appointment recently at a hospital for what I thought was a growth on my tongue (it was just an overgrown taste bud). A trainee inspected me in a chair that looked like it was from a 1950s electric chair with a computerized system that I swear was running DOS.

It probably was running on DOS. The VA “exported” the VistA system to other countries. I put it in quotes because the software is open source. Other countries just adjusted it to their specs and ran with it.

“DOS? You were lucky! When I was treated by the NHS, …” etc etc etc

NHS uses BBC Micros?

I was thinking morel like CP/M.

The example I always use is comparing medical faculties [sic] (public) to dentistry ones (private).

Hell, I don’t even have to go that far. I just ask the person I’m talking to if they have a dog or cat (they usually do), and then ask them to compare the speed and responsiveness of the veterinary clinic they go to for their animals with the human clinic they go to for themselves. It at least gets them thinking, although they then start to get all derpy trying to figure out why that’s an okay state of affairs.

I also had at least one neighbour of mine ask me “how do you know if you’re getting a good surgeon in the private system?” That’s how far the brainwashing has gone for many people here — they think the existence of a publicly-funded system is a guarantee of high-quality medical personnel. Because All-Seeing Eye Of Government or something.

**HEAVY SIGH**

If the government sanctioned it, even a turd polisher is an expert doctor..

They got Kermit Gosnell. Why are they complaining?

Well, they are all licensed the same, so that’s not going to help identify the good ones.

Perhaps a surgeon who can be held personally responsible for their mistakes, working for an organization and/or in a facility that can be held financially liable for poor care, might give a clue as to whether the private or public system is likely to have better doctors?

What are you? An alien?

True.

Advocates of government-run healthcare often tout the moral superiority of the “equality” of government-run healthcare. But here’s the thing: rich people will either use the private system that typically exists alongside the public one, or if no private system exists, they’ll just go to another country. Rich people ALWAYS get the healthcare they need.

The only way to prevent this would be to ban them from getting medical care in other countries, which would probably require banning them from going to other countries… Which I’m sure the “progressives” wouldn’t have a problem with.

Exactly this. You’ll see if you look into it, that several countries have government ran healthcare, but a privately ran system has sprung up alongside it. So anyone who can afford it will use the private system because it’s far superior in every way. The only people using single payer government ran care are people with no other options.

And yes, the progs would gladly ban you from going to other countries. No one needs 3 choices of countries to go to.

I find the best response to what could go wrong is simply “Trump.”

Some how single payer proponents never get to the part where genocidal RepubliKKKans will be running it half the time.

I mainly believe that universal single-payer support exists here because so many people here are at heart uncreative and unoriginal. They look at every fellow Westernized country and say “Hey, they have single-payer and my Canadian friends love it! They say that their average insurance costs are way “cheaper” than over here, why can’t our country have the same thing?” They ignore all the stuff about the insanely high tax rates in these places, the lower standards of living that are in many ways consequences of those high taxes, the way that single-payer stifles pharmaceutical and medical innovation, etc.

Something they miss is the USA is fronting most of the cost of drug development. If there is no profit motive pharma market, who is going to develop the cheap generic drugs.

Space Aliens looking for slave women?

That has nothing to do with the FDA making it take 10-20 years and 5-6 billion dollars to get a single new drug to market.

There’s that, and there’s also the fact that the American healthcare system is always referred to as “free market” when it’s better described as a hodge-podge of government-protected cartels and socialized healthcare schemes with a tiny smidgen of free market remaining. The libertarian’s toughest task is to make people realize that what the US healthcare system suffers from is not an excess of economic freedom.

Chief Kulak Rand Paul tried to explain that on the Today Show, with the expected stammering from the interviewers.

It harshed their narrative, so it couldn’t be true.

Rand’s not a real doctor anyway. Talking media heads know more about healthcare.

Proggess Buttercup: “But Wesley, what about the Republicans Of Unusual Severity?”

Dread Proggy Roberts: “I don’t believe they exist…

Posted in the dead thread: Wife just now after seeing an ad for the Einstien TV show: “I think the main reason the US is so spectacularly successful is because everyone else is so spectacularly stupid. We get all of the best people.”

I think I should stay married to that chick.

I am going to check on my bees. Then I will come back and curse single payer.

One of my favorite Bee Stories –

The Story of St Vespaluus.

I’ve always been of the opinion that Clovis Sangrail would have felt right at home here, if he existed.

People think bugs are stupid, but they aren’t. Not all of them anyway. Bees are social animals and they can read you. They also get to know you. I am wearing jeans and an untucked t-shirt. I took the top of the hive off and inspected. They are doing fine. I put out some sugar for them. One flew up the sleeve of my shirt and one flew up the back of my shirt. They crawled around on me. I fussed and fluffed my shirt. They both crawled up and flew out of the neck of my shirt.

The only time I have ever been stung is when I have accidentally mashed one with my fingers when handling parts of the hive. They know me and know that I am the guy that feeds and houses them. I am the guy that kills wasps, mites and those goddamned hive beetles.

Oh, and when I dont put food out for them I cant have any peace. If I go outside they get in my face and nag the hell out of me.

I was trying to imply that the bees didn’t sting because they either liked the way the guy smelled or figured out that he wasn’t the one that caused their stress.

*removing a bee’s stinger kills the bee, so unlikely explanation.

Oh, and when I dont put food out for them I cant have any peace. If I go outside they get in my face and nag the hell out of me.

Kinda like a wife?

Well, they are all female and frigid….

Clovis certainly has the diction of man accustomed to top hats.

I think the main reason the US is so spectacularly successful is because everyone else is so spectacularly stupid.

Thus sayth the man living off credit card debt.

Ok, then less stupid than everyone else. Tallest midget.

Um, should that say they do worry about it?

For a small clinic, sure. Not so much for hospitals. Per Roemer’s law, the bed will be full. If it isn’t they either overestimated capacity and simply need to identify the demand for another specialty. In the end they go out of business if beds are empty, so they will find a way to fill it.

Besides, outside of rural areas, have you ever seen an empty hospital? The demand will always be there.

The only empty hospital I know of is the Giant VA hospital they built here, but don’t have any surgeons to operate or patients to operate on.

In FL? That can’t be right, “they” keep telling me the facilities in FL are running at max capacity!

I have some friends that work at the VA. They say they are spending an awful lot of time standing around. My favorite is they have an in house overnight CRNA, but they don’t do OB or emergency surgery. They are literally paid to sleep.

We have a similar issue except it revolves around surgeons that don’t perform surgery.

To a greater or lesser extent, that problem exists in every province in Canada — surgeons spend several days a week basically twiddling their thumbs because all of the ancillary “stuff” they need to perform surgeries are rationed in the public systems. This is doubly bad, because surgery is a manual skill, and inadequate operating room time leads to de-skilling of surgeons over time.

In British Columbia, surgeons in the public system get around this little problem by doing private surgeries once their public obligations are done with for the week — thus, most private clinic surgeries in BC are done during the latter part of a typical work week.

Is this it?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eyf97LAjjcY

As someone who works for a large hospital, I can tell you that we obsess daily about our census of patients, where they are, etc., and we expend vast resources trying to get more patients in our beds. Volume is everything for hospitals.

It is highly unusual for hospitals to have every bed full, and actually a pretty bad idea. When that starts happening at my hospital, we call it an “internal disaster”. Having empty beds is business as usual for a hospital; we can’t and don’t want to fill every freakin’ bed. The trick is to have juuust enough patients.

There’s a lot more reasons than that for hospitals with low census. The biggest challenge facing hospitals is doctors – if you have enough doctors admitting patients, you will be fine. If you don’t, you won’t. So, if you have a problem with low census, the answer is almost always to be found in your medical staff. Convincing doctors to switch hospitals is incredibly difficult and typically expensive. Hospitals go out of business more often for overspending on their physicians than because their census was chronically low, although the former can be a result of the latter.

Okay, I concede the point. Everyone worries about timely scheduling, but I doubt you obsesses over it in the same way. For instance, does your hospital trend the “third next available date?”

Not for hospital beds, no. We (nearly) always have some available. Sometimes we run into problems scheduling some of our more specialized operating rooms, but you only schedule those for elective surgeries anyway. ORs are scheduled by and for doctors, who get blocks of OR time, not for individual cases, so we are really looking at who is using their block time, who wants more, etc. Not really a good proxy for patient wait times, because its their doctor who schedules their surgery anyway, not us.

“Third next available date” is a metric for physician practice availability. We track average times until next available appointment (for both new and established patients) in our clinics, mostly as a way to see if we need to hire another doctor. Most of the docs on our medical staff (call it, 580 out of 600) are not employed by us – we have no visibility into their wait times.

OR are easy for us to schedule as I pointed out here, our surgeons don’t do too many surgeries.

Third next available we use to determine future clinical availability, if the average TNA reaches a certain point it starts affecting other areas of the hospital. Mostly the section that coordinates the Choice program, which has a different funding mechanism.

Since we can’t hire as easily, so most of the time the clinics are coordinating with other VA or affiliate providers to handle the load, which takes up a fair chunk of their time.

My essay written 9 years ago on the subject:Is Free Market Medicine Heartless?

“The answer is that it can do a “better” job, but at a cost that will wreck the economy.</em"

I would certainly feel compelled to argue that this statement more likely than not is transitory, because as soon as the machine realizes there are no external or internal controls to what they do, they will devolve into what every other protected government entity has become: a fytw monopoly of takers.

My biggest fear with single payer is the additional laws the will be passed under the guise of preventative care. If we outlaw/tax/regulate this we lower the risk of that.

Get ready for your state mandated high carb diet to fight obesity and diabetes.

Well, it’d give Hillary an opportunity to sell some more books”

“It takes a gastric bypass”

“It takes a psychiatric intervention (to overcome that hoplophilia)”

I see you saw a therapist for some anxiety you had after a car accident? No second amendment for you!

“I see you voted for Trump in 2020. I have your 5150 already written up”

“You’re a libertarian? BAKER ACT!”

Mandatory cholesterol checks! etc etc

Wait wut? mandatory colostomy bags?

Oh, never mind.. I misread that..

Your biggest fear(s) should be the sky high taxes you will be burdened with, the rationing of care, and the lessening of choice and quality. But yeah, I can totally see banning of anything they think will increase the cost, sodium, alcohol, sugary stuff, etc, etc, etc. And when you get older, death panels. Yes those are real, if you are 50-60 you get that surgery you need. If you’re 70-80? Probably not, just take a pill, grandpa. Your use to the great state as a revenue producing biological resource is no longer relevant.

Well yeah those too.

One of the biggest lies the leftist media and their sycophants use is that the cost of healthcare in the USA is the highest in the world. The trick they use to prop up the lie is that they do not include the taxes used to support the systems that they are claiming are cheaper. But just for example, Germany has single payer (also a private system). German’s pay a much higher rate of personal income tax than people in the USA. So they hide that. But the reality is that single payer does not make healthcare cheaper and it makes it much less available. The fact that people can have their taxes raised so much and then believe what they get in return is ‘free’, is just mind boggling. Please let single payer happen in Cali. They did a poll and asked how many people wanted single payer and it was 70+% yes. Then they asked how many people wanted it along with the 15-20% increase in personal income tax and it dropped into the 20s. You know, the 20 percent who don’t pay payroll taxes.

It’s fun to see how fast government stops seeing you as a profit center, and starts regarding you as a cost center.

We need to protect you from your own stupid choices!

This is supposed to be a quote, in case a plagiarism Nazi is floating around…

Here’s your derp of the day on healthcare from DU.

Person makes correct statement, in no way understands why that statement was right.

“The first step to fixing the healthcare system in this country is to remove the profit motive. There should be strict regulations and price controls on all aspects of healthcare. ”

Yes, because that works so well every time it’s tried!

“We need to remove the idea of “socialism” from our medical jargon.”

YES! Let’s practice socialism, but stop anyone from calling it what it is!

thus all the free speech, no hate speech stuff.

describing something accurately isn’t right.

it has to be politically correct.

Progs are so fucking stupid that I don’t understand how they remember to breathe.

Dear Leader of new Progtopia: Yes, we admit, we’re going to control every minute aspect of your life. But don’t worry, you’re a member of a special group, you won’t be going up against a wall or just disappearing for some slight against the great state, that will be those people who voted for Trump or those radical anarchist libertarians, never you, you’re special!

Prog: *bends over* Yes, great masters, may we have more?

It’s strange how only in healthcare, the market leads to spiraling costs. It’s enough for me to question whether there’s not some other cause…

The only thing government can theoretically do better than the market in terms of providing healthcare is making it “universal.” The market will never achieve universal healthcare. Of course, in reality, neither can government.

Well, the government is in no way involved in healthcare now, so it can’t have anything to do with them. I mean healthcare is like the wild west of totally deregulated industries.

I can already tell the progs what they’re getting with single payer. Because it’s already happened / is happening in other countries. But they won’t listen. A bunch of government bureaucrats will be the only winners.

See my comment below re: public education. The cost of education is spiraling upward too, for the same reasons.

One thing I find difficult to understand is the belief that profit incentives drive costs up. If things cost too much, people don’t buy, and you don’t make any profit.

Yes, it’s totally immoral to make money from someone else’s illness. While we’re at it, it’s also immoral to make money off of someone else’s hunger, so privately owned farms, food suppliers, and restaurants should be illegal. It’s also immoral to make money off of someone else’s unfortunate accident, so the government should take over all car insurance and auto repair shops. And it’s immoral to make money off of someone else’s boredom, so all forms of entertainment should be socialized.

tl;dr: You reach some really stupid conclusions if you accept that it’s immoral to make money by offering someone a solution to some negative situation in their life and insist that this solution should be offered for free by the government.

Hammercorps & Akira – I think they’re specifically referring to people like Shkerli (holy fuck, I spelled his name correctly first try), who are scumbags – increasing cancer drug prices 50x when there are no alternatives is a scumbag move, unless there’s a really compelling motive (e.g., the drug doesn’t work except for a small segment of patients, and you have to cover costs). SLD – he should not be prosecuted for this, but it’s a fuckwad thing to do if your company is making money anyway.

that may be the case, but i think the reason the company was *able* to increase prices in that way was because govt was artificially creating monopolies by limiting competition

i’m not interested in defending shkreli personally so much as pointing out that he’s not the actual architect of the system by which such retarded distortions of the marketplace come about.

The fact that pharma price-arbitrage exists at all should be the focus; not that this one guy happened to exploit an obvious opportunity. In a better marketplace, those prices would be setting themselves.

“I think the reason the company was *able* to increase prices in that way was because govt was artificially creating monopolies by limiting competition…”

Totally agree. I shouldv’e pointed that out.

“If.”

I watched the first half of “the red pill” this morning. I find the honey badgers fascinating. Also I was surprised to see such high user reviews on IMDB. I looked up some “professional” reviews and one cited the documentary “Mad Max: fury road” to show how men are the worst and another cited white western men destroying India. No comment on the Great Leap Forward.

Norman Borlaug is spinning in his grave.

Here. Unfiltered deep.

http://m.huffpost.com/us/entry/us_58b9f314e4b0fa65b844b326

Derp not deep. Stupid phone.

I hate you for linking to that.

I hate myself more for reading it.

I’m gonna go play with my dog for a bit and reset my brain.

Sorry. Would you like to read this instead:

https://www.google.com/amp/www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-et-mn-capsule-red-pill-review-20161008-snap-story,amp.html

You’re making my dog’s day, Florida Man.

Nice. I have a pit boxer mix. What a clown boxers are.

That isn’t my pup, just some rando internet picture. Mine is a boxer mix, though. Don’t know what he was mixed with, but whatever it was his daddy was a hell of a lot bigger than his boxer mom.

He’s the dopiest son of a bitch. Best dog I’ve had, even if he did eat my couch.

You know what, it may be retarded to use a poorly written action movie as an argument because you’re too lazy to argue about actual reality, but at least it’s not a Harry Potter reference.

I’m happy I never finished the Harry Potter series. The stupid allusions my idiot generation keeps making fly over my head instead of assaulting the remaining shreds of my sanity.

I read the Harry Potter books like 10 years ago.

What, are they relevant in political discussions now? What have I missed?

You must not read a lot of clickbait articles or stuff generally written by Millennials. Harry Potter has become the standard literature metaphor used by Millennial journalists on the internet. Whereas in ye olden days one might reference a scene from Shakespeare or something, now there’s a consistent theme of “this is just like that time in Harry Potter when…”

Personally I blame the fact that that schools don’t teach history or the classics properly anymore and culture has become so defuse that it’s basically the only thing most Millennials actually have in common.

Not really. The stuff on The Other Site was about as close as I got to Millennial written articles.

Here’s a decent take on the whole phenomena.

Dear god that’s cringeworthy. Sometimes I really hate my generation.

To 26 year old “journalists”, yes, apparently Harry Potter is always relevant.

fuck all my friends who still talk about that shit.

It’s brony levels of dedication to a childrens tale.

Personally I blame the fact that that schools don’t teach history or the classics properly anymore…

It fits my ongoing theory. Idiocracy had the devolution of man wrong. We’re not devolving because of a spread of the lower end of the IQ spectrum. We’re devolving because of a collapse on the upper end of the scale.

I agree with the point about the Classics. If every high school senior in America had to read Gibbon, a lot of our problems would go away.

Not sure that widespread exposure to Gibbon is the solution. Not developing an educational system that – by design – exposes 100% of American schoolkids to postmodernism and critical theory is probably a better objective.

If it can tolerate *also* exposing at least a portion of the nation’s youth to the classics, that would be a plus.

I was thinking less about universities and more about high schools. I certainly wasn’t exposed to critical theory in high school, the education was just shit. I had the benefit of a grandfather who pushed a classical education on me outside of school, most didn’t. Having decent reading lists for high school students and well developed Western history courses would go a long way.

Well, #6.2 is about to go into sophomore year at high school, and one of his subjects this year will be Human Geography, so I took a gander at the syllabus. It includes a unit on “Urban development – Social Planning”. While critical theory isn’t actually being taught, its poisonous branches will sprout buds, if not fruit.

I’m not that worried about him in isolation. He’s been spouting about Hayekian ‘spontaneous order’ for at least a year, but he may get himself into some academic hot water is he can’t resist opening his yap in that class.

But you can bet your sweet bippy that even though postmodernism etc isn’t being taught directly in schools, it’s casting a long shadow over the whole exercise. And it’s no accident.

Well, at least they’re aping the feminists they interview in the movie, because holy shit do they come off bad. Every single one of them could basically be summed up as “no, men don’t have any problems and are just being whining, they just hate women, ignore my clear, thinly veiled hatred of men.” No wonder the director stopped calling herself a feminist. And the best part is I haven’t seen any complaints about those feminists being taken out of context, because that’s completely acceptable to the ideologues who hate this movie.

I haven’t finished it, but I like The feminist that said “of course men don’t have the same reproductive rights. They’re Biologically different”. I’m sure her head would have exploded if you said “of course women have different job preferences. They’re biologically different.”

They even interview Big Red, who I would consider the feminist equivalent of the half-mad aunt you don’t like to be seen in public with, but apparently feminists are just fine being associated with someone that deranged.

I had to work through the technical details in the article, but I think I mastered them.

If you’re a veteran, you can get PCP.

You know, I think those Syrians need to be told who’s boss. If the military will tweak their standards just a little, I’ll go there and fight.

Just so long as the formulary has the *good* PCP.

^^This guy gets it.^^

I think it’s safe to assume any government-run health care system is going to work about as well as our current government-run school system.

I’ve actually heard “progressives” say stuff like that before.

“Why are you so scared of socialized medicine? We already have socialized schools, socialized roads, and socialized police, so why not socialized medicine??”

It’s particularly amusing when they bring up socialized police because “progressives” in 2017 seem to have a lot of complaints about how our police officers do things. They always get that deer-in-the-headlights look when I point out this inconsistency.

An entrenched bureaucracy that is resistant to change, a system that does not reward efficiency or innovation, and difficulty in firing people who do a bad job. What’s not to like?

exactly. with costs endlessly rising, and improvements to the system effectively nonexistent

It’s easy to get lost in the weeds when talking about medical care. Don’t lose sight of the fact that the single most powerful tool for control of the populace is control of medical care. That is what all of this shit is about: control.

I have always believed that this whole push for government control of healthcare and healthcare dollars is so they can pick winners and losers here too.

My simple solution is: let the government be sued the same as any other service provider. The first pot we take from is salaries, pensions and benefits of those identified as culpable, then the travel and training budget of the affected agency, then the general budget of the agency. Also, each congress person loses $100 from their salary each time a successful muitimillion verdict is upheld. (Note, I am expecting them to lose at least $100000 a year from their salaries for the first decade)

SImple, but impossible. I promise you by year 3, Congress would have dissolved everything that wasn’t directly required by the Constitution.

The root cause of all of the problems with government is unaccountability. Bad actors and bad ideas can only live where they aren’t subject to the harm they cause.

If you think the wailing and screaming is bad with Trump, try introducing accountability to government. They would start a shooting war.

“The root cause of all of the problems with government is unaccountability. Bad actors and bad ideas can only live where they aren’t subject to the harm they cause.”

Why do you think that the people that passed Obamacare so we could find out what was in it, gave themselves an exception to following what they foisted on the rest of us, huh?

The reason why the idea of single payer is so popular among progs is that the media and Democrat leaders spew this non-sense 24/7 about how healthcare is better and cheaper everywhere else in the world. And the idiots believe every single thing they’re told without any research of their own, because 1. they want to believe it and 2. they’re fucking lazy. The mainstream media cannot crash and burn fast enough.

You just summed up most of our problems with those two reasons.

After having several proggies I have discussed it with, I can’t help but think the reason government healthcare is so popular amongst that crowd of idiots is that it appeals to a lot of people that feel if they could get healthcare guaranteed by government fiat, they would just opt to live from the welfare system, so they can just quit what they consider to be a rat race, and somehow, miraculously live some top notch lives being bums.

Well, if that’s true, you could quickly disabuse them of that notion by pointing out that Britain is chock-full of bums, many of whom aren’t living that life (entirely) out of personal choice, and don’t enjoy startlingly wonderful health.

tl;dr = u wanna kill the poor

/most of the public

Single payer just died in the California Legislature after they realized it was going to cost more than the state’s entire GNP. If an idea is so stupid an impractical that even California decides its too crazy, it isn’t happening anywhere outside of Evergreen State College.

An idea too stupid for the California legislature? That is surprising.

Some of them (the left) are already starting to whine about how they deserve the help of the federal government to cover the costs and how it’s not fair if they don’t get it. So let me get this right, CA cannot afford single payer unless the rest of the states bail them out. So who is going to bail out the entire country when it goes national? They sure don’t think ahead much, do they? Also, I don’t have a link, but when they did a poll to see how popular the idea of single payer was, 70+%, I think it was actually 78% approved of single payer. Then they did a 2nd poll to see how popular the idea of single payer was with a 15-20% increase in payroll tax to pay for part of it. It then dropped to less than 30%. So lots of people want free stuff until they find out it’s not free. Also, even the 15-20% increase in personal tax, along with large increases in corporate tax is still not enough to pay the bill. Californians, get ready to pay half your income in taxes for shitty rationed healthcare, please let it happen.

Apparently, none of them ever heard of TANSTAAFL.

Ok, I gotta ask – what does that stand for?

There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch.

There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch.

My first intro to the acronym was in one of Heinlein’s works. Can’t remember which one. In turn, according to his bio, he heard it from some guy at a sci-fi convention (or what passed for one) back in the day.

It’s used many times in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, and frequently elsewhere.

Ah yes, My Mistress Harshly Mooned Me. Loved that book.

Oh wait — that was Friday.

You were the guy she left bleeding out in the luggage locker in the first sentence?

Hubba hubba!

God dammit, I was hoping they’d go Full Chavez! This sucks, now they can keep whining for their beloved Single Payer Socialism.

Oh, they still want to go full on commie, they just want the rest of us to pay for it.

I’m sure they’ll float the idea again in the near future.

Not so sure. California doesn’t have the Federal Reserve to print money and magically create value from nothing. That and the populace has been so brainwashed to consider healthcare a “right” and care only about “coverage” not price or quality that I think saying single payer is dead is just whistling past the graveyard.

So the second Project Veritas video is out. This time it is Van Jones admitting the Russian story is bullshit. Am I the only one who confuses Van Jones with Alex Jones? So many crazy people named Jones you can’t keep up.

bill hicks is alex jones is van jones!

iowahawk suggested a few weeks back that some network somewhere needs to create the “Hannity and Mensch” primetime news show. God that would be some spectacular crazy.

I’m sure it was taken out of context.

Context was “I don’t want this recorded”…

The police show up at your door “Sir, someone sent a video tape of you beating your neighbor with a pool cue”. You respond “that was selectively edited and taken out of context!!”

What is incredible is that anyone at all thought the Russia story was ever anything other than bullshit. The Hillary campaign literally just pulled it out of their ass as an excuse for losing an election that should have been a cakewalk. It was always a laughable lie.

The CNN guy on the first tape nailed it. You know they don’t have any evidence of it because if they did, they would have leaked it already. It is all complete bullshit.

Mark Zuckerberg Compares Facebook to Church, Little League

The great thing about Zuckerberg’s delusions about changing the world, is that everyone except him sees how stupid he is.

Well, if Facebook really is like a church, it’s most like the Peoples Temple.

Well, they’ve already started punishing the sinners. Suckerburg is hiring an army of nannybots to delete 66,000 posts, which might be hate speech as determined by …. someone. 66,000, yes that’s the number they used.

How long until they start selling the ability to keep up offending posts? I mean if they are a church, churches could sell forgiveness of sins, and liberals especially when you consider the whole carbon credit scam, really buy into that idea, why not let people pay to keep nasty posts up?

{{{Indulgences}}} ?

Does censoring comments/communities in Germany help strengthen the social fabric too?

Na sicher! Gehorche jetzt!

Is this what that dumbass video was about when I checked FB this morning?

And the thing that made him fabulously wealthy is a blight on humanity.

It’s like giving a Nobel Prize to the guy who genetically engineers a particularly virulent herpes-ebola hybrid.

Nah. Twitter is a blight on humanity. Facebook is just a way for grandmothers to keep in touch with their grandkids. Why do you hate grandma?

She won’t put out?

Not Facebook’s fault Grandma doesn’t think you are cute.

Because she’s dead?

Well, my grandmothers have both been dead since I was 13, so I hold no particular affection for that title.

Well, he did provide a service to all the morons who can get together and convince each other that their stupid dogs and ugly kids are really interesting.

Hilariously, Facebook (and even moreso Twitter) does the exact opposite. Giving people a platform to spew out their immediate, emotional responses to everything does not a community make. There’s no incentives to connect and build relationships with people fundamentally different to you because there’s no benefits in doing so. There is, however, benefits in blocking or unfriending anyone you disagree with politically, morally, etc. and forming a little hugbox collective where everyone agrees with each other and just screams at the other tribes once and awhile to the adoring praise of your fellow tribe members. Twitter is even worse than this because it allows immediate emotional responses, and the character limit basically ensures that you’ll never have an intellectually stimulating comment or discussion outside of the already pithy (i.e. Iowahawk and the like).

Well, it is creating a ‘community’, in the same way as rounding up all the world’s Tourettes’ sufferers and putting them in a huge, echoic dungeon.

That’s my point, it’s not creating a ‘community’ or ‘bringing the world closer together’, it’s creating a series of communities that completely hate each other and will never be able to connect with people outside of their bubble.

I joke that if Zuckerberg runs for office he’ll do so aiming to become the ‘First Autistic President’ but he really seems to fundamentally not understand how humans function in social environments.

If we can do this, it will not only turn around the whole decline in community membership we’ve seen for decades, it will start to strengthen our social fabric and bring the world closer together

That actually is a real phenomenon. I actually discuss it a little bit in the article I’m working on. Since the end of WWII, civic participation has declined steadily. Funny thing is, I can think of a major trend that preceded this decline for about fifteen years and hasn’t let up since.

Hitler?

Close.

http://www.kitco.com/ind/Saville/images/sep252012_1.png

That graph has a really big spike.

Didn’t the idiot who wrote the book about Kansas write another book decrying that people are no longer bowling in leagues?

Thomas Frank wrote What’s the Matter with Kansas, Robert Putnam wrote Bowling Alone.

Thomas Frank was also just forced to resign by CNN. Not relevant here, but damn I like typing that!

It was a different author. And the latter book (it was based off of an essay) was using bowling leagues as an example of a larger phenomenon. And it’s not a bad point. It’s just the author completely misdiagnoses the source of the problem.

Facebook is more like the religious pamphlet warfare of the 17th century.

“The Dogg Returning to its Vomite, or, a Lover of Truth TOTALLY DESTROYES the author of the Lying Pamphlet entitled A Vindication of Presbyterian Principles – clicke here for more”

17th Century pamphlets are juicy as hell. Though I know better the publications around the American Revolution. Great stuff.

So, increasing PC censorship and trying to drag everyone in.

No.

Suck my dick Zuckberg.

How’s that for strengthening social fabrics?

Fricken commie gibberish.

Man, this guy just really nails it.

You want people to die!

Remy is great.

Great to see him back again.

http://www.oregonlive.com/oregon-standoff/2017/06/fbi_agent_indicted_accused_of.html

FBI agent indicted for making false statements and obstruction of justice. Well knock me over with a feather.

the details suggest that its fairly incidental to the events.

he fired at the suspect (Fincum) and then claimed he hadn’t. i assume the reason being that in the immediate aftermath, he believed it was not a good-shoot. so he and his FBI buddies covered it up.

but the actual killing of the suspect is still being treated as a good shoot, and his cover-up is basically being treated as a procedural side-note. so, in essence, i think the greater-crime is being papered over by this lesser one.

Pretty much. But the fact that any FBI agent is being indicted at all is pretty surprising. The whole point of being an FBI agent is to be able to get away with murder not have to take a bullshit wrap for perjury instead.

RIP Gary DeCarlo.

I wonder if they will play the song at his funeral.

When even Politico has gotten wise to the scam that is the SPLC, I think it’s safe to say that the jig is up for Morris Dees.

American progressive shit heads have no clue what they’re talking about when it comes to public health. NONE.

Bunch of idiots. What they’re angling for is mediocre, rationed health.

Period.

“Rationed”? You mean government takeovers don’t turn any industry into an infinite wellspring of high-quality products and services??