On March 6, 1857, a large audience crowded into a room in the U. S. Capitol to hear the justices of the Supreme Court pronounce on the fate of Dred Scott, a black man seeking a legal ruling that he was a free man. Scott claimed he had been liberated from slavery by living in federal territory where slavery had been forbidden by Congress’ Missouri Compromise law. Scott had come to the wrong place. Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney read an opinion declaring that Scott remained a slave, that black people, slave or free, were not citizens, and that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional because it purported to keep slavery out of federal territories.

The following day, Justices Benjamin Curtis and John McLean read their dissents. Not all of the Justices read their opinions on these two days, however. Justice John Archibald Campbell had a written opinion in which he agreed that Dred Scott was a slave.

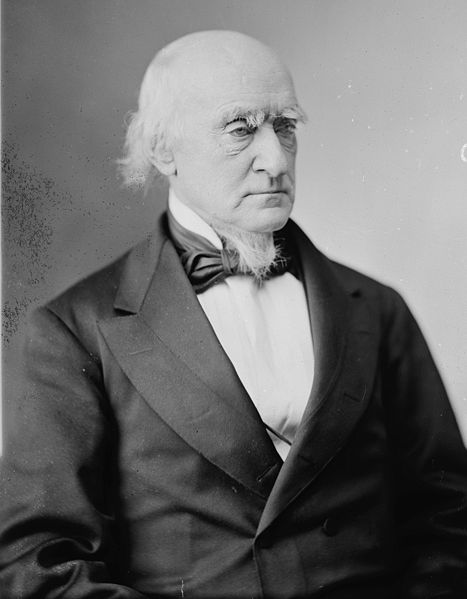

This is the story of John Archibald Campbell – a “fascinating figure” according to the actor Gregory Itzin, the guy who played Campbell in Steven Spielberg’s movie Lincoln. Of course, as an article in startrek.com noted, Itzin is “especially good at being bad, or at least being in league with the villains of too many movies and television shows to count.” So Itzin’s remark doesn’t necessarily count as a character reference. And since Spielberg only gave the Campbell character one line, there wasn’t much chance for Itzin to flesh out Campbell in detail (except through the stern gazes he directed at other characters).

The fact is that the same John A. Campbell who ruled for slavery in the Dred Scott case also (unsuccessfully) promoted a broad pro-liberty interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment in the Slaughterhouse Cases.

It’s not clear whether Campbell agreed with Taney’s view that all black people – slave or free – were categorically excluded from citizenship. Campbell’s opinion in Dred Scott focused on the other key issue of the case – slavery in the federal territories. Here Campbell reiterated views he’d held since about 1850, before he was on the Court – views which had grown mainstream among Taney and other leading Southerners. Although as recently as 1848, Campbell had admitted that Congress could ban slavery in the federal territories, two years later Campbell proclaimed the opposite doctrine.

Concerned with Northern attacks on the South in the name of antislavery, Campbell in 1850, as in 1857, said that a Southerner who settled in a federal territory had the right to hold his slaves there as “property,” just like a Northern settler had the Constitutional right to hold his farm implements, cows, and pigs as property. Campbell believed that this was an issue of equal rights – the Southerner must have the same right to his version of property that the Northerner had to his version. Defending slave-owning as a matter of equal rights – that’s some messed-up s*** right there – but it’s what most elite Southerners had come to believe.

Campbell actually thought slavery was on the way out. In articles he wrote in his pre-Court days, he said that the spirit of the age in America, as well as the South’s need to shift from agriculture to commerce and industry, would lead to the end of the Peculiar Institution. But sudden emancipation, such as urged by Northern abolitionists, would (Campbell believed) lead to bloodshed and economic disaster – as in Haiti. To gradually ease out of slavery, Campbell wrote, the Southern states – without Northern meddling – should prepare slaves for freedom by giving them at least a basic education, protecting their families from being broken up by sale, and preventing creditors from seizing an owner’s slaves. But as Northern pressure against slavery increased, Campbell believed that Southerners’ priority should be to resist this outside pressure and defend slavery against Yankee attacks.

Before being appointed to the Supreme Court, Campbell had been a prominent attorney in Mobile, Alabama. He made his reputation by defending clients who owned valuable land next to the Mobile River. In arguments ultimately accepted by the state and federal Supreme Courts, Campbell said that Alabama, when it became a state in 1819, acquired the right to dispose of these lands regardless of interference from the federal government – a position which established Campbell’s clients’ title to the land as well as putting Campbell on the states’ rights side of a key issue.

From 1849 to 1853, Campbell appeared many times before the U. S. Supreme Court – mostly losing his cases but impressing the Justices with the quality of his preparation and legal argument.

Campbell was also active in the Southern Rights Association, a group which warned Southerners of the dangers posed by Northern opponents of slavery in the wake of the extensive conquests of the Mexican war. Anonymous pamphlets by Campbell (on behalf of the Mobile branch of the Southern Rights Association) warned that Northern fanatics were trying to prevent Southerners from settling in the new territories with their slaves, as was allegedly their constitutional right. A fellow-Alabamian, William Lowndes Yancey, was a leader of the Southern rights Association and had previously worked with Campbell. Yancey was a leading “fire-eating” supporter of Southern rights and of a separate Southern nation.

Campbell put some distance between himself and Yancey at an 1850 convention of Southern leaders, held at Nashville to consider the danger posed by Northern antislavery initiatives. Many of the resolutions passed at the Nashville convention were drafted by Campbell, and took what in the political climate of the time was a conciliatory tone in comparison to Yancey’s secessionism. The Nashville Convention resolutions warned the North that it must allow slavery in the territories and otherwise respect Southern “rights.” But any talk of secession was declared premature. Compromise measures approved in Congress should be given a chance to work. The resolutions were vague on whether secession would ever be a good idea.

When Democratic President Franklin Pierce took office in 1853, he had to fill a Supreme Court vacancy left by the death of John McKinley of Alabama. After looking around for a good nominee, Pierce selected Campbell, who came recommended by all but two Southern legislatures. Also backing Campbell, in a historically-rare endorsement, were the remaining members of the Supreme Court, who requested that the guy who had impressed them so much as an advocate should come up and sit on the bench with them. Pierce and the Senate agreed and put Campbell on the Court.

One of Campbell’s Supreme Court would have denied citizenship…to corporations. If Campbell was correct, then the right of corporations to sue in federal court would be severely curtailed. But Campbell’s opinion was in dissent, and the Court majority, then as now, said corporations are citizens with broad rights to invoke the protection of the federal courts.

Not that Campbell supported states’ rights in all cases. Like other Southern leaders, he turned into a virulent nationalist when it came to fugitive slaves. Campbell believed the federal government, under Congress’ strong Fugitive Slave Law, should send U. S. marshals to arrest black people in the North, give them a brief and inadequate hearing to decide if they were fugitives from slavery, and then ship them off to their alleged masters, without regard to any Northern state laws which tried to protect the civil liberties of accused black people. Campbell joined a unanimous Supreme Court opinion that state courts could not hear habeas corpus petitions from federal prisoners – including alleged fugitives and their Northern rescuers.

To Campbell, the enforcement of the federal Fugitive Slave Act was a matter of justice which the North owed to the South. The South, meanwhile, should reciprocate by helping the feds fight filibusters.

No, not that kind of filibuster. More like this:

Private American “filibuster” armies were organizing throughout the country, particularly in the South, in order to invade Latin American territory. Campbell thought the “filibuster” leaders were seeking to expand slavery and add new slave territories – like Spanish-held Cuba – to the United States.

In those days, Supreme Court justices had duties as trial judges, and Campbell was assigned to hear federal cases in Mobile, Alabama, and in New Orleans in neighboring Louisiana. So when Campbell came to New Orleans in 1854, he told the federal grand jury to go after the filibusters, particularly former Mississippi governor John Quitman and his associates, who were plotting an attack on Cuba.

Campbell indicated the concerns which motivated him. He told the grand jury that just as Southerners rightly demanded that Northerners put aside their antislavery feelings and let the Fugitive Slave Law be enforced, Northerners rightfully demanded that Southerners let the federal Neutrality Acts be enforced against the filibusters.

Quitman and his associates were summoned to testify before the grand jury, but they took the Fifth, and the grand jury didn’t indict anyone. But Campbell put the kibosh on Quitman’s Cuban raid by forcing the would-be filibusters to post large money bonds – the money would be forfeit if Quitman and crew waged private wars against other countries. Quitman had to give up his plans, and he spared no invective against Campbell for his allegedly oppressive actions. Campbell later tried to take proceedings against the filibuster William Walker, but did not stop Walker from ruling Nicaragua as a slave country (until he got shot, which wasn’t Campbell’s fault).

The filibuster-sympathizers in the South, of whom there were many, grew hostile to Campbell.

Campbell became distressed at what he considered a conspiracy of Southern disunionists. These conspirators, in Campbell’s telling, started plotting secession around 1858. According to Campbell, filibusters joined up with supporters of a revived African slave trade in a scheme to set up a slave republic in the Southern United States and the Latin American territories they conquered. There was certainly one person thinking along these lines – William Yancey, Campbell’s former political ally from Alabama. But Yancey wanted to break up the Union, while Campbell wanted to keep the country together, so long as this could be accomplished peacefully.

After President Lincoln was elected in November 1860, Campbell wrote what he thought were some private letters declaring that secession was at best premature. Lincoln’s election was not in itself an act of aggression against the South, and if the federal government seemed about to adopt antislavery measures, the Southern states could consult together as they had in 1850, rather than getting into a mad rush to secede. Campbell’s “private” letters were published, exacerbating the hostility against him from red-hot secessionists in Mobile and elsewhere.

Alabama voted to secede in January 1861, joining several other Southern states. Campbell decided not to resign from the Supreme Court, but to stay in Washington, D.C., and try to broker some kind of compromise which would avoid war. After Abraham Lincoln took office in March, Campbell, sometimes backed up by his Court colleague Samuel Nelson of New York, offered his good offices in soothing tense relations between North and South.

The new Confederate States of America had sent commissioners to Washington, but the Lincoln administration would not recognize them. So Campbell (and sometimes Nelson) served as go-betweens between the commissioners and William Henry Seward, the Secretary of State. Seward had been the country’s most prominent Republican before Lincoln came on the scene, and the former New York governor saw himself as basically Lincoln’s prime minister. Seward also saw himself as a peacemaker – by conciliatory gestures, he thought he could isolate the secessionists and rally support among Union-loving Southerners.

Seward gave assurances to Campbell and Nelson that the federal authorities would soon evacuate Fort Sumter, the federal fort whose presence in Charleston Harbor had become a source of serious friction between the two sides. With Seward’s permission, Campbell conveyed the Secretary’s assurances to the Confederate commissioners and to Jefferson Davis. Later, when Fort Sumter was obviously not being evacuated, Seward told Campbell that Lincoln was under pressure from hardliners not to withdraw, but at least the feds would give advance warning before resupplying the fort. What had actually happened is that Lincoln had made clear that he, not Seward, was President, and that Seward’s peace overtures were unauthorized. Seward retained considerable power in the administration, but no longer as an independent policymaker.

In the end, the Confederates concluded that United States forces wouldn’t leave Fort Sumter unless they were forced out, and thus the Civil War began.

Campbell, understandably feeling duped by Seward, concluded that his usefulness as a peacemaker was at an end, and that his place was with the South. He resigned from the Supreme Court and moved to New Orleans, a friendlier city to him than Mobile. Campbell planned to resume private law practice.

New Orleans was an important Southern port. It also had some serious public health problems, though Campbell didn’t know the future relevance of this fact to his career. People dumped their garbage and excrement in the streets and in parts of the Mississippi which fed the municipal water pipes. Butchers dumped carcasses and offal in the river or even used their waste to fill holes in the street. Physicians and the various public-health boards before the war had issued repeated warnings that this situation was linked to the periodic outbreaks of cholera and yellow fever which almost routinely hit the city, endangering residents who weren’t well-off enough to evacuate until the infection ran its course.

The war temporarily improved the situation, though Campbell probably didn’t appreciate the way the improvements happened. In 1862, Union forces conquered the city, and General Benjamin Butler became the Union commander in occupied New Orleans. A bad general, Butler could be a good administrator and, at least in the North, a good politician. His harsh measures against Confederate sympathizers (treating rebel-sympathizing women like prostitutes, for instance) made him hated in New Orleans, but Butler did the Crescent City a favor with vigorously-enforced sanitary regulations.

Sanitary or not, Campbell for his part didn’t want to be in a Union-occupied city, and he moved to Richmond, VA, the Confederate capital. It is possible that, due to Campbell’s fame as a U.S. Supreme Court Justice, President Jefferson Davis might have appointed Campbell to the Confederate Supreme Court. However, there was no Confederate Supreme Court to which Campbell could have been appointed. The Confederate Congress refused to authorize such a Supreme Court, concerned that such a body would diminish the powers of the state courts. Another factor might have been that many of the solons didn’t like Campbell and didn’t want him to be a Justice again.

Instead, Campbell got a position as Assistant Secretary of War. He would help the War Department in its administrative work, provide legal opinions, and administer the Confederate conscription program.

The most significant part of Campbell’s legacy at the Confederate War Department was his campaign to protect the rights of conscientious objectors. Here Campbell manifested a sense of justice toward religious pacifists who refused to be drafted into the Confederate army. The conscription statute allowed members of recognized peace sects – Quakers, Mennonites, Dunkers – to be exempt from service upon payment of a hefty fee. Some pacifists could not or would not pay the fee, while others got screwed around by military authorities and were dragged into the army where the statute no longer protected them.

Campbell worked assiduously to make sure that religious pacifists had the chance to pay their commutation fees, and to receive civilian assignments which were consistent with their consciences, and even to get discharged from the army if they had been forcibly mustered in – this latter initiative on Campbell’s part went beyond the letter of the conscription statute. Lobbyists for the various peace sects knew who to call when any of their members faced draft problems. This was useful because the Quakers, in particular, could not necessarily count on sympathy with Confederate authorities due to the well-known Quaker opposition to slavery. Campbell for one was happy to help Quakers, and he had a good working relationship with John Bacon Crenshaw, a Quaker leader in the Richmond area who brought the cases of both Quakers and non-Quakers to Campbell’s attention.

Self-portrait of Cyrus Pringle, American botanist and Quaker pacifist – he was tortured during the Civil War for refusing to submit to conscription. John A. Campbell tried to protect people like Pringle from being persecuted for their consciences. (click the picture or see the alt-text for punch line)

Campbell drew the line at draft-dodgers who merely pretended to be religious pacifists – the Quakers and others saw an upsurge in membership applications at this time. Campbell warned officials not to recognize phony pacifists in religious clothing.

Campbell also fumed that certain state courts were ordering the release of conscripts deemed improperly drafted. Getting in touch again with his inner nationalist, Campbell denied that state courts could interfere with Confederate prisoners, just as he had denied that state courts could interfere with U.S. prisoners.

At one point, a would-be assassin wrote the War Department, offering his services in bumping off Lincoln. A good bureaucrat, Campbell routinely forwarded the letter to the appropriate official, and the assassination plan was ignored.

Working in the Confederate War Department was not nearly as lucrative as private law practice in the South or a Supreme Court justiceship in Washington. With a salary measured in Confederate currency, and with inflation in Richmond, it would not have been a comfortable existence. And the whole Confederacy was in a bad condition: attacked, blockaded, and losing territory (like New Orleans) to a richer, more populous enemy.

By December 1864, Campbell was convinced that the Confederacy was a Lost Cause, and he wrote North to Supreme Court Justice Samuel Nelson, his former colleague, saying that an “honorable peace” should be worked out. Nelson replied that peace talks were already in the works.

President Lincoln was being pressured by an influential supporter, the old Jacksonian Francis Preston Blair, to seek peace talks with the South. Lincoln couldn’t afford to alienate Blair, so he allowed Blair to sound out Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who seemed quite receptive.

The Confederacy was collapsing all around Jefferson Davis, morale was low, and Davis was being criticized from all quarters. Yet Davis had not had a Steiner Moment. He still thought the war was winnable, if only he could rally the people behind one more grand effort. What better way to revive the public’s patriotism than to show that Lincoln was seeking a complete, humiliating surrender? And what better way to get the necessary proof of Lincoln’s evil intentions than by sending a delegation of known peaceniks to attempt negotiations with Lincoln? That would show Davis’ domestic opposition that there was no way forward except continuing the war under Davis’ leadership.

So the Confederate President responded to Blair’s initiative. Davis picked three peace commissioners known for their opposition to his war policy: Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens, Confederate Senator R. M. T. Hunter…and Campbell. The three commissioners crossed Union lines and met Lincoln and Seward aboard the boat River Queen near Hampton Roads, Virginia.

There followed four hours of friendly conversation, but the two sides were far apart. Lincoln was committed to negotiate peace in “our one common country,” while Davis’ instructions spoke of negotiating peace between “the two countries.” Campbell, pragmatically, didn’t adhere to Davis’ delusions and instead raised practical issues about the terms of a Northern victory. Would Reconstruction of the former Confederate states be harsh or lenient? Would Southerners who had lost property – not just phony “property” like slaves but honest to goodness property like land, farm animals, and so on – get restitution or compensation?

Campbell’s realism contrasted with the time-wasting weirdness of others. Hunter said Lincoln should negotiate with his domestic foes like Charles I did, virtually inviting Lincoln’s zinger that Charles had lost his head. Stephens and Seward mulled over Francis Blair’s Quixotic plan for a joint Union-Confederate expedition against the French in Mexico. Lincoln insisted that the Confederates would have to stop fighting and rejoin the Union. The meeting ended with everyone on good terms, but they were no closer to a peace deal.

As the commissioners were departing, Seward had a black sailor row a boat over to give the commissioners a gift of some champagne. In a remark worthy of Blanche Knott’s Truly Tasteless Jokes, Seward called out to the commissioners to “keep the champagne, but return the Negro.” (This incident didn’t make it into Spielberg’s movie.)

Davis, as he had probably planned all along, sought to rally the public by telling them of Lincoln’s intransigence. These pep talks didn’t stop the inevitable.

Soon after Campbell’s return to Richmond, the Confederate government evacuated the city. Campbell remained behind as federal troops moved in, and the ex-Justice again tried to take up a peacemaking role. Campbell hoped that Lincoln would let the old Confederate states keep their existing governments once they rejoined the union, and that these states would be spared military rule.

Lincoln came to Richmond on a visit, giving Campbell a chance to take the matter up with the President in person. Campbell suggested that if the pro-Confederate Virginia legislature agreed to put Virginia back in the Union, soldiers from Virginia would lay down their arms. Lincoln liked this, and he gave orders that the legislature could meet under Union protection for the purpose of pulling Virginia troops out of the war. This suggested at least a de facto recognition of the Virginia legislature, a key step toward mild Reconstruction and hopefully, Campbell thought, serving as a precedent for other states.

Campbell had out-negotiated Lincoln, but it made no difference, since Lincoln had the guns and could alter the agreement at will. After Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Lincoln, facing denunciation for his softness toward the rebels, reconsidered the deal with Campbell and blocked the meeting of the Virginia legislature.

After Lincoln’s assassination, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton believed that the killing had been plotted by Confederate higher-ups. So when a search of captured Confederate archives found that Campbell had bureaucratically handled a letter from a would-be assassin, that was enough motive to order Campbell’s arrest. Not to mention that Campbell had embarrassed Northern hardliners by trying to get Lincoln to endorse a mild reconstruction. So Campbell was imprisoned without trial at Fort Pulaski, in the harbor of Savannah (GA), for several months.

Several influential people supported Campbell’s freedom in petitions to the new President, Andrew Johnson. The Dunkers praised Campbell’s protection of the rights of conscientious objectors. The Quakers, after overcoming reservations about supporting freedom for a “traitor,” joined in appealing for the release of their former benefactor. Campbell’s old Supreme Court colleague Benjamin Curtis, who had disagreed with Campbell in the Dred Scott case, added his voice in favor of Campbell’s release.

Finally, the feds let Campbell return to Mobile. The local citizenry was still mad at him for supposedly being a traitor to the South, so Campbell got federal permission to relocate to New Orleans, where he began building a successful law practice. He did this through his usual work ethic and by attention to the details of his cases, ultimately rebuilding the wealth he had lost during the war.

At first Campbell’s practice was limited to state courts, because Congress required lawyers who wanted to practice in federal court swear they had never supported the Confederacy. Campbell, of course, could not swear this. The U. S. Supreme Court, however, said that Congress’ law was unconstitutional, so Campbell could practice in federal courts again.

A prominent New Jersey lawyer wrote his daughter from New Orleans in April 1867, when he was paying a brief visit to the city. “Everybody here, of the old residency, is secessionist in feeling,” in the view of Joseph Bradley. The former slaves, stirred up to new levels of assertiveness by the federal Freedman’s Bureau, were refusing to work at rates the plantation owners could afford, and without black workers “the plantations will become a desert waste.” Back up North, Bradley dropped those sad musings when supporting General Ulysses Grant’s successful campaign for President in 1868. Bradley said that electing Grant was necessary to stamp out the “destestable heresy” of states’ rights and affirm the “paramount sovereignty” of the federal government.

Around the time Campbell regained his right to practice in federal courts, he lost his right to hold public office. Congress adopted the harsh Reconstruction policy which Campbell had tried to avert. The former Confederate states were put under military rule until they adopted modern constitutions, allowed black men to vote, and ratified a new constitutional amendment, the Fourteenth. The Fourteenth Amendment, adopted in 1868, provided in Section 3 that prewar officeholders who joined the Confederacy would be forbidden from holding state or federal office. Campbell remained a private citizen, doing his part to oppose the new order of things.

Louisiana elected carpetbagger Henry Clay Warmoth as governor and a Republican-majority legislature containing numerous black members. Writing to his daughter Katherine, Campbell said that “[w]e have the Africans in place all about us” as “jurors, post office clerks, customhouse officers, and day-by-day they barter away their obligations and duties.” It doesn’t take a diversity-training course to recognize this as racism – Campbell was casting reflections on the capacity of black people for self-government.

Many of the clients Campbell took on in New Orleans filed challenges to various parts of the legislative program of the Reconstruction legislature. Campbell spearheaded the legal offensive against these laws passed by what he deemed an illegitimate government. Campbell’s initial strategy was to seek out sympathetic trial judges in New Orleans and obtain injunctions against the policies he was challenging. A Republican state Supreme Court would ultimately overturn the injunctions and allow the laws in question to be enforced, but that allowed for a good interval in which Reconstruction policies were inoperative. The legislature got wise to Campbell’s tactics and created a trial court with the exclusive responsibility of handling these challenges to Reconstruction. This was Judge Henry C. Dibble’s court, which we’ve encountered in the account of the Sauvinet case.

During this time, Campbell took on his most famous case.

After the U. S. military stopped enforcing General Butler’s sanitary regulations, prewar filthiness returned to New Orleans, including the return of epidemics. The Reconstruction legislature took a crack at reform, borrowing an idea used in many other big cities. The slaughtering of animals was to be confined to a particular location, a system deemed safer than letting butchers dump carcasses and offal just about anywhere.

Under the statute, butchers would have to slaughter their animals at the specified location, at a slaughterhouse run by a state-chartered private corporation. This corporation was limited in the fees it could charge the butchers, but even so, it possessed a government-granted monopoly. Ronald M. Labbé and Jonathan Lurie, historians otherwise sympathetic to sanitary reform in New Orleans and to the Louisiana Reconstruction government, say that the company’s leaders used corrupt methods to get the needed votes in the legislature.

The butchers hired Campbell to challenge the slaughterhouse monopoly . Campbell claimed the law basically enslaved the butchers by requiring them to use a particular slaughterhouse. Campbell, the former defender of slavery, was prepared to invoke the Thirteenth Amendment on behalf of his clients.

Campbell also urged a broad reading of the Fourteenth Amendment, with a definition of the privileges and immunities of citizenship broad enough to protect the right to earn an honest living. With the Fourteenth Amendment so broad, it would also protect the rights in the Bill of Rights.

Campbell’s clients lost in the Louisiana Supreme Court in April 1870, so Campbell got permission to take the case to the United States Supreme Court. On May 15, Campbell’s daughter Mary Ellen died suddenly, probably from one of New Orleans’ yellow-fever outbreaks. Campbell had little time to mourn, because on June 9, he was in the federal circuit court then meeting in New Orleans. Campbell wanted the circuit court to issue an injunction, so that the slaughterhouse law wouldn’t be enforced until the U. S. Supreme Court could weigh in on the case.

The circuit court consisted of Judge William B. Woods and the newest Supreme Court Justices, Joseph Bradley. The New Jersey lawyer had been commissioned as a Justice in March, and Bradley was responsible for riding circuit in Louisiana and five other Southern states, though his experience with the South was limited to his 1867 visit.

Bradley granted the injunction, giving an opinion which indicated where he stood on the case. After initial hesitation, Bradley said that the privileges and immunities of United States citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment included the right to earn a living, free from government monopolies such as the one the Louisiana legislature had created.

In a case of true irony (Alanis Morissette take note), Bradley’s main client in private practice had been a railway monopoly in New Jersey. The so-called Joint Companies had the exclusive right to carry passengers and freight north and south through the state. New Jersey got a cut of the profits, allowing state taxes to remain low. The ones to suffer from the arrangement were other companies, and the travelers and shippers who could have benefited from more competition. Bradley had zealously defended the Joint Companies’ monopoly as a lawyer/lobbyist, invoking states’ rights arguments to prevent the federal government from establishing competing railroad lines, even during the war emergency. Now like Prince Hal with Falstaff, Bradley had cast off his association with the Joint Companies upon becoming a Justice.

Campbell had to go to Washington to argue the Slaughterhouse Cases. And he had other reasons to come to Washington besides appearing before the Supreme Court. After the Louisiana elections of 1872, rival candidates for governor and other offices declared themselves elected. Campbell was part of a “nonpartisan” committee whose members happened to be Democrats. The committee complained about how the Republicans had stolen the election from the Democrats with the aid of the Grant administration and the federal courts. It was no use – Federal troops continued to back the Louisiana Republicans.

Meanwhile, Benjamin Butler, now a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, put a bill through Congress restoring political rights to most of the ex-Confederates who had been affected by Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. The bill kept a few categories of people under political disabilities, including prewar federal judges who had joined the Confederacy. Campbell came under this ban, and though he could have applied for an individual pardon from Congress, he contemptuously declined to do so, focusing on his legal practice and his Democratic political activism (these two things were linked).

In his Supreme Court argument, Campbell said that compelling the butchers to use a specific slaughterhouse was a form of slavery or involuntary servitude, contrary to the 13th Amendment. Probably aware that the 14th Amendment argument would get taken more seriously, Campbell put particular emphasis on it, especially the clause protecting the privileges and immunities of citizenship from state infringement.

The Fourteenth Amendment had been adopted just in time, argued Campbell, because as the franchise was extended, there were more ignorant voters.

The force of universal suffrage in politics is like that of gun powder in war, or steam in industry. In the hands of power, and where the population is incapable or servile power will not fail to control it, it is irresistible. Whatever ambition, avarice, usurpation, servility, licentiousness, or pusillanimity needs a shelter will find it under its protection influence.

Campbell suggested that in places like Louisiana, crooked politicians manipulated the support of ignorant voters to push through bad, self-interested laws.

The 14th Amendment was “not confined to any race or class,” Campbell argued.

It comprehends all within the scope of its provisions. The vast number of laborers in mines, manufactories, commerce, as well as the laborers on the plantations are defended against the unequal legislation of the States. Nor is the amendment confined in its application to the laboring men.

Businessmen – including butchers – were protected as well.

[C]an there be any centralization more complete or any despotism less responsible than that of a State legislature concerning itself with dominating the avocations, pursuits and modes of labor of the population; conferring monopolies on some, voting subsidies to others, restraining the freedom and independence of others, and making merchandise of the whole?

In the Court’s internal deliberations, Justice Bradley argued the cause of a broadly-construed Fourteenth Amendment. Bradley’s adversary was Justice Samuel Freeman Miller. Both Bradley and Miller had been appointed by President Lincoln, but their judicial philosophies were very different.

Miller viewed the Confederates – specifically including Campbell – as unreliable traitors, and he backed the Fourteenth Amendment as necessary to protect blacks and white Unionists from Southern oppression. But Miller didn’t think states’ rights were a Confederate monopoly. In his home state of Iowa, Miller saw what happened when the federal government trampled on states’ rights.

Before the war, many Iowa communities, including Miller’s hometown of Keokuk, issued bonds to build railroads. Rail commerce was supposed to be an economic boon, but Keokuk and other places found the whole thing economically a bust. The bondholders still wanted their money. Iowa’s highest court said the bonds had been forbidden by state law, so the taxpayers were off the hook. The U. S. Supreme Court, however, said that Iowa law did authorize the bonds.

Miller dissented because interpreting state law is the business of state courts, not federal courts – but as a trial judge Miller felt reluctantly bound to enforce his colleagues’ majority decision. This meant putting municipal officials in prison for standing up for the taxpayers and refusing payment on bonds which Iowa courts considered illegal. You didn’t have to be a Confederate to object to that sort of federal overreaching (which the Supreme Court itself repudiated a couple generations later). Perhaps one thing Miller may have agreed with the prewar Campbell about was that corporations could do much mischief if given broad access to the federal courts.

Miller developed a hostile attitude to “capitalists,” whom he defined as “those who live solely by interest and dividends.” Apparently Miller blurred the distinction between crony capitalists and honest capitalists.

As if that weren’t enough to make Miller skeptical of the butchers’ claims, Miller used to be a country physician in Kentucky, and had seen the effects of cholera, including the deaths of two of his law partners. Miller linked disease outbreaks to unhealthy slaughterhouse disposal practices.

One of Miller’s less desirable characteristics, according to his generally sympathetic biographer Michael A. Ross, is that “Miller adjusted his legal arguments to meet practical political and economic ends, rather than adhering to a consistent judicial ideology.”

The Supreme Court divided 4-4 on the Slaughterhouse Cases, the ninth Justice being Samuel Nelson, who had once joined Campbell in trying to play peacemaker between North and South. The elderly Nelson left the court in 1872, so the Court reconsidered the Slaughterhouse Cases once President Grant had appointed Nelson’s replacement. This replacement was Ward Hunt, a New Yorker backed by political boss Roscoe Conkling. The undistinguished Hunt later became so incapacitated that Congress awarded him a full pension in exchange for his immediate retirement. But in the first year of his term, Hunt sided with Miller and upheld the Louisiana slaughterhouse law.

Justice Miller delivered the opinion. To Miller, Campbell’s broad view of the Fourteenth Amendment would make the Supreme Court into a “perpetual censor” on state legislation. Miller said that the Amendment had been passed to protect freed slaves and their descendants and would probably be only rarely invoked for any other purpose. The privileges and immunities protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, Miller said, were rights of United States citizenship, not of state citizenship – the latter rights were subject to state regulation. The privileges and immunities of U. S. citizenship did not include the right to earn an honest living – business regulation was a state matter. But there were some privileges and immunities of federal citizenship, and Miller listed a few traditional civil liberties.

Justice Bradley repeated and expanded on the views he had expressed in 1870, and in the course of arguing for a broad definition of Fourteenth Amendment rights, he indicated that these included the right to earn an honest living as well as the rights mentioned in the Bill of Rights:

The Constitution, it is true, as it stood prior to the recent amendments, specifies, in terms, only a few of the personal privileges and immunities of citizens, but they are very comprehensive in their character. The States were merely prohibited from passing bills of attainder, ex post facto laws, laws impairing the obligation of contracts, and perhaps one or two more. But others of the greatest consequence were enumerated, although they were only secured, in express terms, from invasion by the Federal government; such as the right of habeas corpus, the right of trial by jury, of free exercise of religious worship, the right of free speech and a free press, the right peaceably to assemble for the discussion of public measures, the right to be secure against unreasonable searches and seizures, and above all, and including almost all the rest, the right of not being deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. These and still others are specified in the original Constitution, or in the early amendments of it, as among the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States, or, what is still stronger for the force of the argument, the rights of all persons, whether citizens or not.

While Campbell lost the Slaughterhouse Cases, Miller’s narrow interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment was helpful in another case Campbell took on. Here, Campbell’s clients were prosecuted for their part in a massacre.

In Grant Parish (Grant County as non-Louisianans might call it), two rival candidates for sheriff claimed to have won the election. Black residents supported the Republican claimant, and white residents supported the Democratic/Warmothite (Fusion) claimant. Both groups of supporters, deputized by their respective candidates, faced off against each other. The better-armed whites defeated the blacks and massacred many of the survivors. The “Colfax Massacre” raised enough outrage that the Grant administration prosecuted some white perpetrators for violating the blacks’ constitutional rights, including the right to bear arms (the whites had demanded the blacks disarm) and the right to assemble peacefully.

“The Louisiana Murders—Gathering The Dead And Wounded” – published in Harper’s Weekly May 10, 1873, page 397 after the Colfax massacre in Colfax on April 13, 1873.

The white defendants were convicted, and Campbell was one of the lawyers who prepared their appeal. Campbell made free use of the Slaughterhouse precedent. The rights to peaceful assembly and bearing arms were not privileges and immunities of United States citizenship, argued Campbell, but of state citizenship only, hence not protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. Also, the crimes were private acts by private persons, and not committed by a state, and the 14th Amendment did not apply.

Justice Bradley, one of the judges hearing the case at trial, reaffirmed that the privileges and immunities of citizenship includes the rights in the Bill of Rights, such as peaceful assembly and bearing arms. But Bradley went on to say that the violators were acting as private actors, not on behalf of the state, and that private actions could not be punished unless motivated by racism (which the indictment didn’t specifically allege).

The Supreme Court agreed in the Cruikshank decision and went further than Bradley. There was no federal right to bear arms, the Court said. As for the right to assemble, that was only a federal right if you assemble to petition the federal government for a redress of grievances. The Court’s views on the Bill of Rights were narrower than Bradley’s, but this time Bradley did not protest, for whatever reason.

When Democrat Samuel Tilden ran against Republican Rutherford Hayes for the Presidency in 1876, the results of the election turned on competing results from several states, including Louisiana. Campbell defended Louisiana Democrats in the Electoral Commission which had been appointed to resolve the crisis. While the Republican state government in Louisiana had certified Hayes the winner, Campbell said Congress should not defer to the states. Again putting on his nationalist hat, Campbell said Congress should overrule the Louisiana authorities and discard fraudulent Republican votes. The Commission declared Hayes the winner by an 8-7 margin. Hayes’ 8 votes came from the Republican members of the Commission, including Justices Joseph Bradley and Samuel Miller, who were voting on the same side for once.

The South agreed to accept Hayes’ election as President in exchange for Hayes withdrawing federal troops from the South. This betrayal upset Justice Miller, who unburdened himself in a letter: Miller said he had “rendered fifteen years of faithful irreproachable service” to the Republican Party since his appointment to the bench in 1862. But now Miller was so disappointed in the Republicans that “I shall hereafter feel myself at perfect liberty to oppose or disapprove of any may or any measure as my judgment may dictate.” Better late than never, I guess.

Without federal troops to support the Republicans, Louisiana was “redeemed” (taken over by racist Democrats).

Campbell moved to Baltimore where he could better conduct a legal practice which focused on appearances before the Supreme Court. He died in 1889.

If Campbell had held on for another nine years, he would have finally had his political rights restored in 1898, when a Congress flush with bro-hugging patriotism during the Spanish-American war gave an amnesty to all living ex-Confederates who still needed it. Subsequent action by Congress indicates that Campbell’s legal disabilities are still in force: In 1978 a Congressional resolution restored the office-holding rights of Jefferson Davis who, like Campbell, had died unpardoned before the 1898 amnesty. But I am not aware of any such posthumous resolution being enacted for Campbell’s benefit. Therefore, as far as Congress is concerned, Campbell is still barred from holding office under the terms of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Congress did name the federal district courthouse in Mobile after Campbell in 1981. In 1983, the local U. S. magistrate published an article to enlighten Alabama lawyers with a brief account of the “varied” career of the man after whom the federal courthouse was named. Probably for the sake of emphasizing the positive, the article summarized Campbell’s Supreme Court career this way: “The Supreme Court decisions of Justice Campbell are of little interest to us, but it is accurate to say that they are well-written and reflect his consistent strict-constructionist and state’s rights views.”

Another federal courthouse building is currently being added, and the Campbell building is being renovated, so that the two buildings will make a “campus” where justice will be even more justice-ier.

The John Archibald Campbell United States Courthouse in Mobile, Alabama, 9 September 2012. Photo by Chris Pruitt

Works Cited

“An Act to Designate the John Archibald Campbell United States Courthouse.” Public Law 97-126, December 29, 1981, 95 Stat. 1674. Online at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-95/pdf/STATUTE-95-Pg1674.pdf.

David A. Bagwell, “The John Archibald Campbell United States Courthouse in Mobile,” 44 Ala. Law. 154 1983 (May 1983).

Peter Brock, Pacifism in the United States: From the Colonial Era to the First World War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1968.

“Catching up with Frequent Star trek Guest Gregory Itzin, August 2, 2012, http://www.startrek.com/article/catching-up-with-frequent-trek-guest-gregory-itzin

Richard C. Cortner, The Supreme Court and the Second Bill of Rights: The Fourteenth Amendment and the Nationalization of Civil Liberties. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1981.

John B. Crenshaw Papers, Hege Library, Guilford College, Greensboro, NC, available online at http://library.guilford.edu/c.php?g=210067&p=1385778

Richard Nelson Current, Those Terrible Carpetbaggers. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Jonathan Truman Dorris, Pardon and Amnesty under Lincoln and Johnson: The Restoration of the Confederates to Their Rights and Privileges, 1681-1898. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1953.

John Witherspoon DuBose, The life and times of William Lowndes Yancey. A history of political parties in the United States, from 1834 to 1864; especially as to the origin of the Confederate States, volume 2. New York: Peter Smith, 1942.

Don E. Fehrenbacher, Slavery, Law, and Politics: The Dred Scott Case in Historical Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.

Shelby Foote, The Civil War: A Narrative: Red River to Appomattox. New York: Vintage Books, 1986.

General Services Administration, “Mobile Courthouse Groundbreaking,” March 25, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DQ9nxC01zeA

Ronald M. Labbé and Jonathan Lurie, The Slaughterhouse Cases: Regulation, Reconstruction, and the Fourteenth Amendment. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003.

Charles Lane, The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, The Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction. New York: Henry Holt, 2008.

Charles McClain, California Carpetbagger: The Career of Henry Dibble, 28 QLR 885 (2009), Available at: http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/facpubs/660.

Russell McClintock, Lincoln and the Decision for War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Robert E. May, John A. Quitman: Old South Crusader. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1985.

____________, Manifest Destiny’s Underworld: Filibustering in Antebellum America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Justin A. Nystrom, New Orleans after the Civil War: Race, Politics, and a New Birth of Freedom. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

William H. Rehnquist, The Supreme Court: How it Was, How it is. New York: William Morrow, 1987.

Michael A. Ross, Justice of Shattered Dreams: Samuel Freeman Miller and the Supreme Court During the Civil War Era. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003.

______________, “Obstructing reconstruction: John Archibald Campbell and the legal campaign against Louisiana’s Reconstruction Government,” Civil War History, September 2003, pp. 235-53.

Robert Saunders, Jr., John Archibald Campbell, Southern Moderate, 1811-1889. Tuscaloosa, The University of Alabama Press, 1997.

Steven Spielberg (dir.), Lincoln. Dreamworks Pictures, 2013.

Walter Stahr, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012.

Eric H. Walther, The Fire-Eaters. Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

“Ward Hunt,” https://www.oyez.org/justices/ward_hunt

Robert Penn Warren, Jefferson Davis Gets His Citizenship Back. University Press of Kentucky, 1980.

Ruth Ann Whiteside, “Justice Joseph Bradley and the Reconstruction Amendments,” PhD Thesis, Rice University, 1981.

Edward Needles Wright, Conscientious Objectors in the Civil War. New York: Perpetua, 1961.

1) tl;dr – this is getting a little ridiculous. is there going to be a quiz?

2) OG neckbeard FTW

I don’t think that’s a neck beard. It’s more like chest hair out of control. As you can see by the brows and hair, the guy is not that into the grooming thing, except for shaving the face.

you’re tripping, yo.

classic 19th century neckbeard

It’s great how I can learn almost in real-time how readers react…then I can assimilate the reaction and adapt.

If I get around to my next one, I think you’re gonna like it better.

I’ll read it… eventually. my lunch-reading needs to be more terse.

Eddie, while I really do appreciate your attention to detail, this is a rather long article for a blog.

Yeah, that beard is strange. It’s like the inverse of an Amish-style chinstrap. Anyone got a specific name for that?

Ignore the haters, Eddie!

It was a great article.

I’m going to save it for my bus ride tomorrow morning. I love this kind of stuff. Thanks, Eddie

In contrast to certain sites Not To Be Named, I pay attention to readers’ concerns. Please stay tuned, and if they let me, you might see my next bright idea.

Needz moar virtue signal.

I thought I was doing marketing hype – or maybe it’s the same thing?

Oh come now, do not patronize us. We are not your typical commentariat. We know full well that you writers will be giving each other awards soon enough and then dare I say, cocktail parties.

Ok, who leaked our secret nefarious plans to that blabbermouth Hyper?

There is a reason I chose to break up my project into smaller more digestible bits. Also, to ensure a continuous stream of delicious content for the site.

I may do that.

Indeed, sometimes we must sacrifice for the target medium. Great article otherwise, I enjoy histories.

If that man is not the visual inspiration for Sam the Eagle then I officially give up.

http://vignette3.wikia.nocookie.net/muppet/images/0/07/Sam_Eagle.JPG/revision/latest?cb=20110117133053

If not for the big nose, the guy bears an uncanny resemblance to my 85 year old father.

It’s articles like this that make me wish I could view the site on my work computer.

No way I’m scrolling through that again on my phone.

Huh. I live five minutes outside of Colfax. That massacre, little known, is still remembered here and there are some hard feelings. A lot of local people, black and white, have ancestors that were involved in that.

Hey, I resemble this.

Nice name.

Relative of yours?

(throws gang signs)

*makes wiggle sizzle for rizzle*

Good articles Eddie.

I’d like to see some others contribute. We have some pretty good candidates around here for in-depth discussions on inalienable rights, jury nullification, libertarian objection to the licensure for the exercising of rights, etc…solid cases for core libertarian stuff to counter the kind of slander that is out there and counter the fakers. I can write about all of those but I am far from the most qualified.

Agreed. Wish I could, but I’m not really qualified to write about anything, unless you wanted to find a libertarian angle in corporate personhood or establishment of the SEC and the 1933 and 1934 acts.

Those sound good, they’re quite pertinent.

Yeah, something to rebut the blithering idiocy about corporations from the SJW tards would be nice.

I’d be happy to put something together on the history of corporate personhood and corporate law in the US, once I get through proxy season (next week or two)

I had you in mind RC

Don’t let that stop you, Suthen. Just because a topic is covered here once doesn’t mean it can’t be revisited later in more depth or from a different angle.

I’m overdue for an article here. My apologies to all.

You should get an advanced degree in history, Eddie. If you don’t already have one.

…just because the question once came up on a different angle –

what value does any official-certification offer the ‘amateur’ historian? If a person can produce scholarly work already, what’s the point of getting a sheepskin providing some rubber-stamp of approval? Unless your goal is to work in the academy, i’d think any advanced degree is just paying professors to grade work you were going to do anyway.

Fair enough.

But, once you get your advanced degree you can make up any sort of horseshit you want and publish it with no repercussions, and if someone questions you, you can simply show them your masters degree from columbia and send them on their way.

An advanced degree automagically makes you like twenty eleventy times more smarter. If you don’t believe me, ask someone who has one.

I have one, and I am definitely smart than you.

/sickburn

No, I wanted someone who could actually say that and be serious.

/sickerburn!

*sigh*

…Than you ARe. Smarter than you ARE.

^Skitt’s law^

Every time I think 19th century facial hair needs to make a comeback I’m provided with a horrible example that makes me question it again.

No need for a silk scarf when you have a luxurious neckbeard.

Ambrose Everett Burnside scowls at ye.

Burnside. He’s staring at the Bridge. He has to get across that damn bridge.

Where’s that confounded bridge?

That’s quite an outlandish style. It looks like all of his hair fell off the top of his head and landed on his face.

I can see where it swivels, near the ears.

That’s not a neckbeard. It’s his pet ferret.

My go to book for Civil War history is

Battle Cry for Freedom

It tries to encompass the entire war, including the roots of the conflict. I’m sure there is, due to the breadth of the subject, some details missing but still a good read.

*for = of Freedom

My all time favorite is Bruce Catton’s Trilogy. It’s like a novel how beautifully it’s written.

I’ll check it out.

I second this. Bruce Catton is great.

because i do not have patience for afternoon links –

Some “just made up 5 minutes ago-institution” publishes a poll showing “1-in-3 Muslims Lives in Fear of Trump Administration”

I expect you will see this ginned-up metric thrown around a lot by MSM pearl-clutchers.

Maybe apropos = you know what else 30% (or so) of Muslims believe?

or just cancel this, and i’ll put it in the newly-posted PM links

I think its mildly amusing given that Dutch tourism relies heavily on “weed + women”

“Of course I *meant* to say they spent large parts of their budgets on booze and women, and wasted the rest.”

Thanks. I really enjoyed that.

Great article, even though I had some trouble following some of the legal terminology and cited cases.

This reminds me of a question I’ve had since high school when learning about the Civil Rights era, which I suppose is relevant to today what with all the fascists burning and punching things because Milo.

Are individuals, not acting on behalf of a local, state, or federal government capable of “violating the civil rights” of another individual? The Constitution is properly understood to be a limit on government authority, so wouldn’t it follow that only laws (and those that enforce them) are capable of violating someone’s right to speech, assemble, arms, etc.? I had always heard that white racists during the 1960s were found guilty of violating the civil rights of blacks. Is that just a lazy way of saying “they were guilty of kidnap and murder”?